China’s Paradox Under Xi - Episode 7 of 7

A Sea /xi:/ of Macro Imbalances - a Story Told Through the Lens of its Bust Property Bubble.

Let us continue our journey on China.

Before we continue, let us briefly recap over view on China as explained in the past six episodes (1) here, (2) here, (3) here, (4) here, (5) here and (6) here:

China’s real estate sector represents 25% of the Chinese economy, 70% of Chinese household wealth and 36% of local government revenues. But today, China’s real estate sector faces huge challenges: the equivalent of one and a half Japan standing vacant, one Netherlands available for sale and nearly one United States remains to be completed. Worst, local government revenues from land concession sales are in free fall and have to be replaced with more (future bad) debt.

In order to deflate this bubble, China’s households and private sector economy face a painful and prolonged de-leveraging process in which companies will stop borrowing despite record low interest rates. Instead of maximizing profits, they will minimize risk by paying down debt - a so called “balance sheet recession”. This is happening right now; China is in a balance sheet recession.

However, the investment-led growth model of the CCP that caused the property bubble and widespread industrial overcapacities remains in place. For the past two decades, China’s capital formation has been hovering around 45%. No other G20 economy came even close to such a high number. The CCP is, and remains, in the middle of an unprecedented macroeconomic experiment in human history that has gone largely unnoticed.

The model worked wonders while animal spirits were in full swing due to higher property prices each year. But it also led to significant malinvestment, diminishing returns on investment and a mountain of debt that will prove hard to service. In 2023, China’s total system debt stood at 318% debt-to-GDP, a level comparable to advanced economies but held within the system fragility of an emerging market economy with Chinese characteristics under a “Marxist” leader. Worse, the current economic model does not allow China to reduce its debt-to-GDP. Quite a toxic cocktail.

There are only 5 paths China’s economy can follow going forward: (1) it can stay the course and take on more debt. We have explained why that must lead to a form of Great Depression as seen in the U.S. in the 1930s. (2) China can replace malinvestment with consumption. In episode 5 we explained, however, why Xi is NOT interested in this approach. Instead, he has steered the country to the Leninist-left, as we like to call it. This has basically left China in a form of collective depression when looking at the CPI and GDP deflator for the past 3 years.

China is highly unlikely able to replace malinvestment with quality growth (4). While it isn’t hard to see China’s authoritarian economy succeeding in some of its new industrial endeavors, it is impossible to know if it can and will deliver enduring productivity gains. The Soviet Union, for example, was no slouch when it came to science, space, engineering and research & development. And yet, these were not enough. The optimistic view is that with Xi Jinping fully focused on new technologies productivity benefits, China will emerge to boost Total Factor Productivity (TFP).

Our view is more pessimistic. It is that the political environment under Xi Jinping is significantly different from what it was during previous transformative reform periods and after WTO membership. The strong emphasis on the personal power of the president and the sharper social and political repression will make it highly unlikely that China can ‘innovate itself’ out of the demographic decline, property bust, bad debt, massive youth unemployment and a middle-income trap it is currently finding itself in.

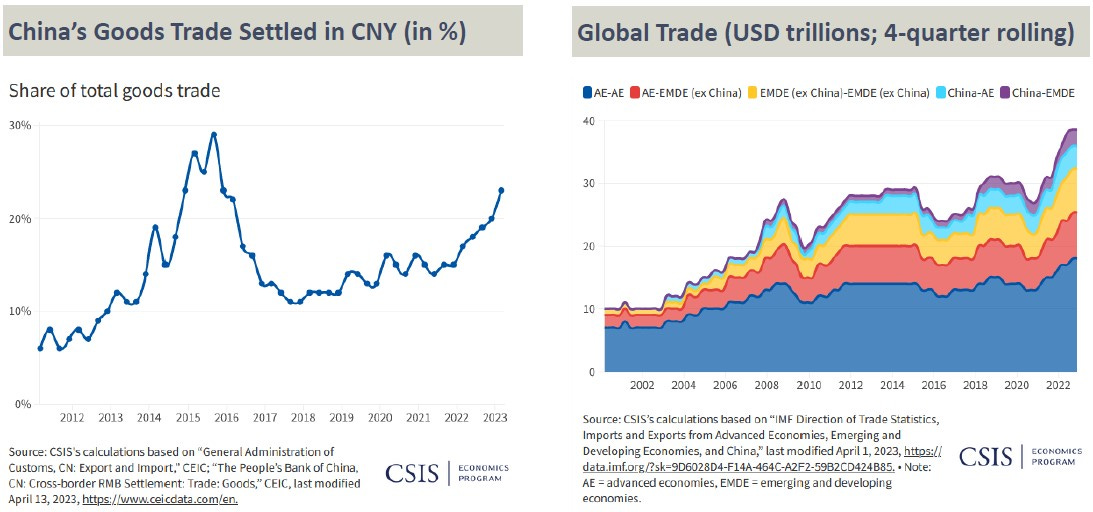

Nor can China export itself out of malinvestment (4). While the official line to take speaks about ‘inwardly focused growth’, in reality the lack of domestic demand condemns China to double-down on its investment-led growth strategy in the green-shift sectors of photovoltaics, batteries and electric vehicles. The publicly stated aim is to gain global dominance in these products. But cars aren’t refrigerators. They touch heartstrings and stir emotions. This will cause escalating trade tensions globally, especially in high value-added sectors such as automotive.

Meanwhile, subsidies keep the price of Chinese goods cheap, flooding global markets and displacing indigenous products and jobs. As a result, the low wages in China and higher unemployment in the West suppress global demand.

China’s economic system is not compatible with the West. A new Cold War 2.0 will be the inevitable result. The election of Donald Trump has made an escalation more likely. But remember, we aren’t in the wine and cloth world anymore. We are in the supply chain world.

Finally, China can (5) replace malinvestment with “do nothing”. The post Soviet Union great depression would be the obvious outcome which we see no need to explain further.

Our view, as expressed in our Episode 6, was that the most likely outcome of combining paths (3) and (4) will not be sufficient for China to succeed.

Given all that, let us now elaborate on two distinct themes that the CCP is affecting: the role of US Dollar as a reserve currency and the global monetary system.

Bonus Chapter 1: De-Dollarization?

Recent debates about the US dollar’s demise or the ascendancy of the renminbi oscillate between extremes instead of answering two distinct questions, both with very different thresholds.

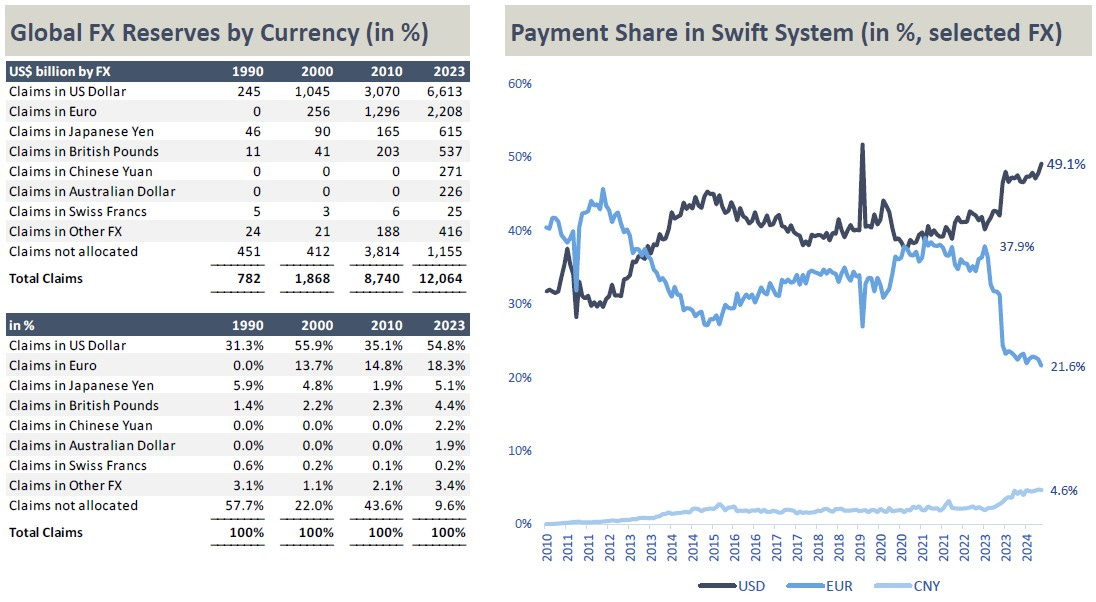

The first question is about high-threshold internationalization: Can the CNY overtake the USD to end its dominance? The answer is, of course not.

This level of CNY internationalization is impossible under the current political system as it would require to liberalize the Chinese economy, including having open Capital Accounts and a sustained trade deficit so that other countries could accumulate CNY claims on China. Expressis verbis, the CCP declared such a level of liberalization a threat to its monopoly on power. It won’t happen while its lifetime chairman runs the country.

The second question is about low-threshold internationalization: Can China encourage enough trade settled in renminbi to boost its standing as a bilateral currency and to reduce its reliance on the US dollar? The answer to this question is, yes, at least at the margins.

However, the risk of devaluation restricts the yuan's potential as shown by the drop following 2015’s devaluation. The implications of these two questions and outcomes are also very different. If the high-threshold question were resolved in renminbi’s favor, China’s global influence would substantially increase at the cost of the United States’ influence.

But again, this won’t happen while under the CCP. If the low-threshold question were answered in the affirmative, China can mitigate potential future US sanction risks. This is clearly work in progress as it matters to Xi Jinping.

Note: China is settling more trade in renminbi. This share increased to roughly 23% of China’s total goods trade as of the first quarter of this year. However, it remains well below its peak in 2015. Back then, China’s exchange rate devaluation and subsequent strengthening of capital controls reduced many businesses’ willingness to settle in and hold renminbi. China’s central bank does not report the countries with which China is conducting trade in renminbi, but the increase in 2022 was likely because of Russia and perhaps a few other countries preferring to hold renminbi due to Western sanctions.