China’s Paradox Under Xi - Episode 6 of 7

A Sea /xi:/ of Macro Imbalances - a Story Told Through the Lens of its Bust Property Bubble.

Let us continue our journey on China.

In this episode, we will discuss whether China may abandon the current investment-led growth model that created significant malinvestment and record indebtedness and replace it with more quality investments and / or exports.

Before we continue, let us briefly recap the property picture as explained in the past four episodes (1) here, (2) here, (3) here, (4) here and (5) here:

China’s real estate sector represents 25% of the Chinese economy, 70% of Chinese household wealth and 36% of local government revenues. But today, China’s real estate sector faces huge challenges: the equivalent of one and a half Japan standing vacant, one Netherlands available for sale and nearly one United States remains to be completed. Worst, local government revenues from land concession sales are in free fall and have to be replaced with more (future bad) debt.

In order to deflate this bubble, China’s households and private sector economy face a painful and prolonged de-leveraging process in which companies will stop borrowing despite record low interest rates. Instead of maximizing profits, they will minimize risk by paying down debt - a so called “balance sheet recession”. This is happening right now; China is in a balance sheet recession.

However, the investment-led growth model of the CCP that caused the property bubble and widespread industrial overcapacities remains in place. For the past two decades, China’s capital formation has been hovering around 45%. No other G20 economy came even close to such a high number. The CCP is, and remains, in the middle of an unprecedented macroeconomic experiment in human history that has gone largely unnoticed.

The model worked wonders while animal spirits were in full swing due to higher property prices each year. But it also led to significant malinvestment, diminishing returns on investment and a mountain of debt that will prove hard to service. In 2023, China’s total system debt stood at 318% debt-to-GDP, a level comparable to advanced economies but held within the system fragility of an emerging market economy with Chinese characteristics under a “Marxist” leader. Quite a toxic cocktail.

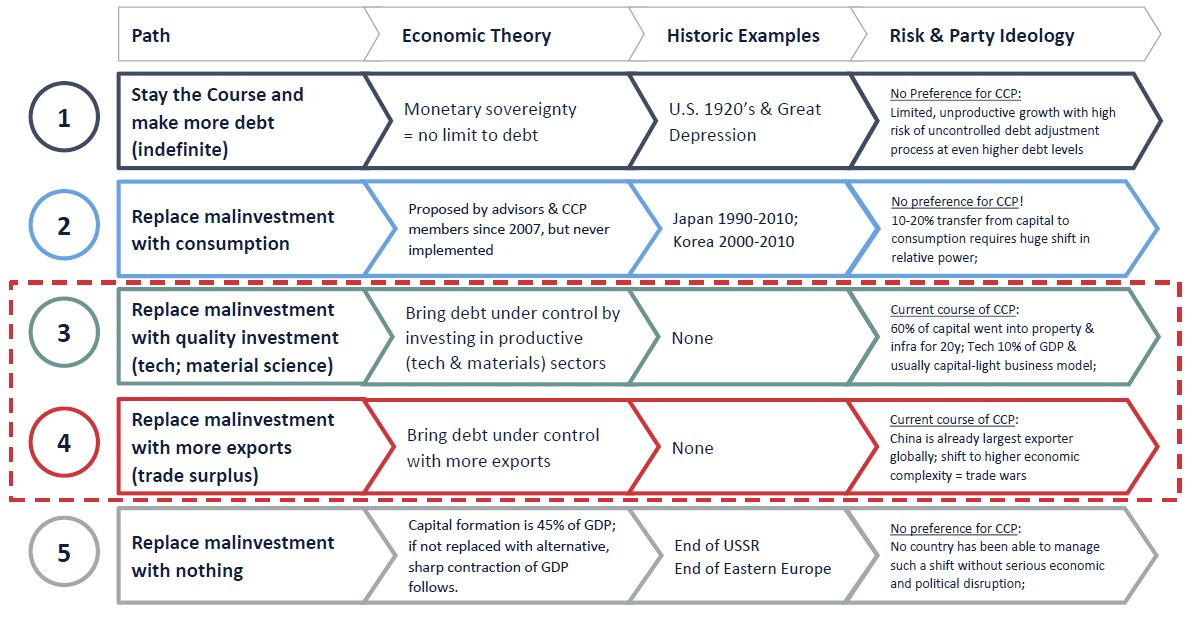

There are only 5 paths China’s economy can follow going forward: (1) it can stay the course and take on more debt. We have explained why that must lead to a form of Great Depression as seen in the U.S. in the 1930s. (2) China can replace malinvestment with consumption. In episode 5 we explained why Xi is not interested in this approach. Instead, he has steered the country to the Leninist-left, as we like to call it. (3) China can replace malinvestment with quality investments or (4) it can replace malinvestment with more exports. The latter two paths are unprecedented in economic history but they are what Xi is pursuing.

Finally, China can (5) replace malinvestment with “do nothing”. The post Soviet Union great depression would be the obvious outcome.

Let us now assess paths 3 and 4.

Path 3: Replacing Malinvestment with Quality Growth

Can China replace malinvestment with quality investment? Yes, it can and will do so partially. But can it replace the entire GDP component of a collapsing property and construction sector? Of course not.

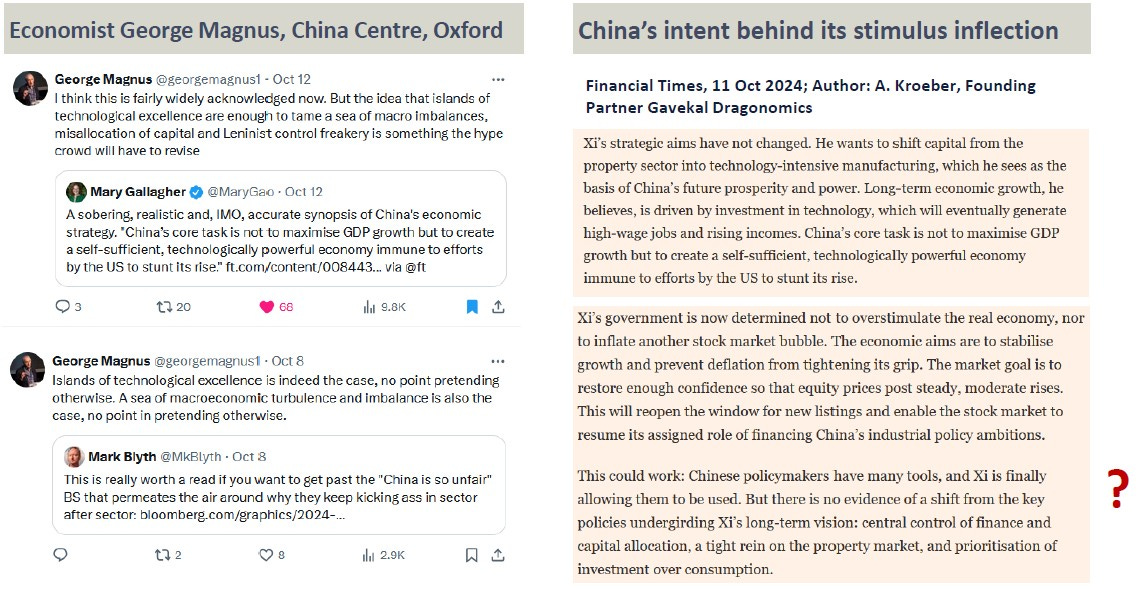

Among China watchers, Xi’s current path – a combination of paths 3 and 4 – is widely acknowledged and clearly outlined in the 14th 5-Year plan. Likewise, nobody sane doubts China’s pockets of (tech & material science) excellence, nor the virtues of the Chinese people.

However those are irrelevant, as succinctly put by George Magnus, former Chief Economist at UBS and a Research Associate at the China Centre, Oxford University:

“The idea that islands of technological excellence are enough to tame a sea of macro imbalances, [sic] malinvestment and Leninist control freakery is something the hype crowd will have to revise”

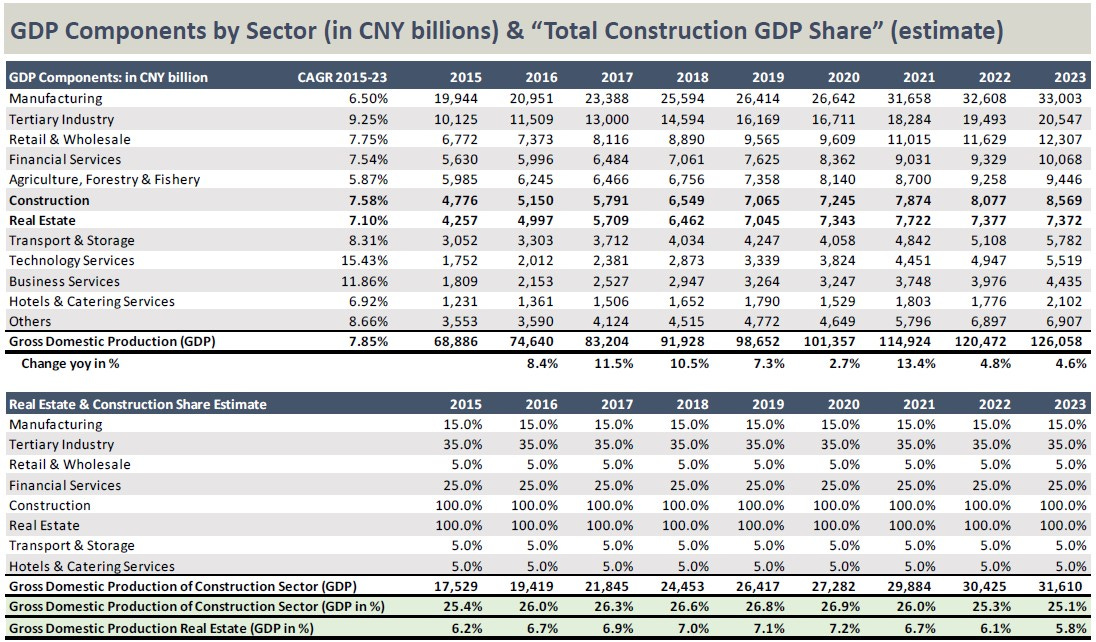

China’s Real Estate GDP share is 6-7%, as reported by the National Bureau of Statistics. However, that figure neither accounts for related cement, steel, or copper output nor for the production of durable goods and other related services, such as financial intermediation to accommodate the sector.

We estimate that, during the period 2015-2023, the total “construction sector”, including infrastructure projects such as roads or airports amounted to 25-30% of China’s GDP.

Analysis by Goldman Sachs found that three of the main industries Xi is giving priority to - namely EVs, lithium-ion batteries and renewable energy - account for only about 3.5% of China’s GDP. They are not nearly big enough to replace China’s property sector.

They also are not big enough to create enough jobs for millions of college graduates and migrant workers who are now struggling to get by. Were BYD to overtake Toyota and Volkswagen as the largest car manufacturer with 100% exports (to avoid domestic substitution effects), it would add 1.7% to GDP. Add solar & battery exports, and we may get to 3%. Property was 25% for decades.

Yes, property won’t collapse to zero overnight. But neither will the “New Three” grow 7-fold overnight. It’s wishful thinking.

If China wants to continue to grow, to become a stable and prosperous high-income country, it will need a new economic strategy. There are historical examples: many now highly successful countries and territories also got their start by relying on unskilled labor. South Korea or Taiwan, for example, developed strong manufacturing sectors and quickly grew from countries rife with poverty to stable economies that provide their citizens with high living standards and strong institutions. Can China do the same?

We hope so, but we fear it won’t be possible under Xi Jinping. In their excellent book “Invisible China: How the Urban-Rural Divide Threatens China's Rise” Scott Rozelle and Natalie Hell make important points which the CCP prefers you not to advertise: “For all the wise decisions the Chinese government has made in recent decades to bring about China’s rapid rise - decollectivizing, building roads and public transportation, investing in labor-intensive industries, and opening the nation to foreign investment - it has failed to invest enough in its single most important asset: its people.”

Today China may be the second largest economy in the world, but it has one of the lowest levels of education of any nation and contrary to popular belief. Data for 2023 from the OECD Education GPS shows only 36.6% of the Chinese workforce attained a secondary education. That compares with 81% for the OECD country average. The average length of education received by the working-age population was 10.2 years in 2015 and was only slightly up to 10.8 years in 2020, according to the World Bank. It doesn’t matter which data series we pick. They are all lower or much lower than any country at China’s level of development, and even lower than many poorer countries.

Some may argue that this is the opportunity. But an increase in total years of schooling of China’s working population hinges on the education levels of younger cohorts. For example, for the age cohort of 20–24 years, there is a 0.3 year increase in the average years of schooling between two consecutive years, reflecting the expansion of education coverage and participation in recent years. However, herein lies the problem. Looking ahead, with the demographic headwinds China is facing, the age composition of the labor force will be changing with lower shares of younger cohorts.

Poor education standards of working class people is a macro economic challenge. In his excellent book ‘Red Flags’, George Magnus correctly points out that the key for future Chinese growth remains total factor productivity (TFP). In a nutshell, China, like many ‘middle-income trapped’ countries, is faced with the challenge of having to boost its TFP.

A brief explanation would be helpful here because TFP isn’t actually measurable. It is, in fact, a residual in GDP growth accounting, once we have accounted for the more measurable contributions made by changes in labor and capital inputs. It is basically an efficiency term that captures the impact of technical progress and institutional arrangements that enable total GDP growth to exceed the sum of its labor and capital parts.

Consider, for example, things like changes in knowledge and ‘know-how’, as opposed to information: the impact of new technologies on new products and processes; competition rules, the operation of the rule of law, and the security of contracts; the way factories or offices are organized; business processes and management techniques; and the effects of high levels of trade and commercial integration. These aspects all enter into economic accounting gymnastics, and are subsumed under TFP.

Many countries in Asia are outward-looking, financially stable, and have a sharp focus on trade, innovation, infrastructure and technology. At the same time, however, they have the challenge of aging, under-utilization of women at work, and inadequate social safety nets. Their entrepreneurship culture is weak and bankruptcy regimes are often poor. Other shortcomings include human capital formation, distortionary trade and state-owned enterprise policies, and inadequate attention to the rule of law. China under Xi fits all of these descriptions.

Again, Xi’s China - as we explained in our last episode in detail - moved domestic politics towards the ‘Leninist left’, economic policy shifted to the ‘Marxist left’, and foreign policy has become more confrontational and assertive, in a move toward the ‘nationalist right’. The key here from a TFP context? Xi is micromanaging China. That will not improve the TFP part contributing to GDP growth.

Of course, in the past, China’s TFP has occasionally been remarkably strong. The first such period was the early 1980s, Deng Xiaoping’s years of reform and opening up, when it grew by nearly 5% per year and accounted for almost half of China’s growth.

After this, it slumped in the period spanning the Tiananmen Square protests, but then surged again between 1991 and 1995 to over 7% a year, as state-owned enterprise reforms were pursued and migrant flows from farms to factories picked up (see graph above). During this phase, TFP was generating about three-fifths of Chinese growth.

Later, in the wake of accession to the WTO, TFP moderated to about 4% per year (about two-fifths of economic growth) until 2010. Since then, however, it has been anemic, growing by about 2% per year until 2015, and subsequently even less.

As George Magnus correctly explains in Red Flags, there are many things that China has proven to be successful at doing in the past, but which it can no longer repeat because they were one-off accomplishments. For example, China could only join the World Trade Organization once. It could only embark on a massive real estate ownership and investment boom once. It could only enroll all of its children in secondary school once. Exploiting the demographic dividend, benefiting from rural-urban migration, and raising the share of employment in industry and manufacturing to peak levels were all achievements that could only happen once. Nor will riding the wave of powerful globalization during the 1990s and 2000s go-go days repeat under Xi, for the reasons we explained above.

Although the CCP’s investment-led growth strategy was hugely effective for three decades, the engine of growth has finally run out of gas. Today China’s unskilled wage rate is rising rapidly. Although higher wages are good for workers in the short run, in the long run this climbing wage rate is going to bring an end to China’s comparative advantage in low-skilled, labor-intensive production. In a globalized world when wages rise, companies simply find cheaper labor elsewhere or (increasingly) find a way to automate.

That’s what’s happening in China today. Every month, tens of thousands of workers are being laid off in China’s key industries. Construction is slowing precipitously. Samsung has moved hundreds of thousands of jobs from China to Vietnam. Nike is now making most of its tennis shoes outside China. This exodus is occurring across the board—in textiles and toys and tools and Christmas decorations. Ten years ago, almost every product for sale in an American Walmart was made in China. Today that is no longer the case. Meanwhile, the spread of new robotics and automation technology is further driving down demand for the Chinese factory worker. And Xi Jinping doesn’t have a good backup plan. He doesn’t even have a social system in place for them.

Nobody questions the virtues of the Chinese people. Even the usually critical of China “The Economist” recently devoted a special edition to it. Today, China leads the world in physical sciences, chemistry and Earth and environmental sciences, according to both the Nature Index and citation measures. Applied research is a Chinese strength too. The country dominates publications on perovskite solar panels, for example, which offer the possibility of being far more efficient than conventional silicon cells at converting sunlight into electricity. But where are the necessary jobs, profits, multiples and market caps?

If indigenous tech innovation (not intellectual property theft at industrial scale) needs to save China from future deflation (and it failed 2023-2024), then its challenge is not just to be the world leader in AI, robotics or driverless vehicles, but to encourage the disruptive changes wrought by general-purpose technology and thus harness productivity benefits across the board.

China may well become a leader in mass-surveillance technology. But it won’t sell such products to its own consumers, nor will it export such technology to the West. Our point? There remains a big question mark whether Chinese consumers can afford, or are even allowed, to harness the benefits of other, more useful technology innovations in China under Xi so as to make it a global tech leader and save its economy from deflation — even if it were successful in the tech innovation cycle.

The fundamental issue is whether a communist political system with a Leninist structure is able to guide innovation, disruption and its consumer adoption at scale, or whether it is in fact the antithesis of what makes these things happen.

We are convinced it is the latter in the short-, mid-, and long-term.